This article was written for the course History and Philosophy of Science 2024.

Alfred Kinsey and the Kinsey Scale

by Jelka Pospig

In this essay, I will briefly portrait Alfred C. Kinsey (1894 – 1956), subsequently explore the influence of the Kinsey Scale on the societal perception of sexual orientation in the 20th and 21th century and finally discuss what advantages and disadvantages labeling of sexual orientation can bring. I argue that Kinsey paved the way for a society more open towards various sexual orientations. Furthermore, I contend that sexual orientation labels can be of personal and societal importance, thus should not be discarded. However, they should be used consciously so that they do not define the entirety of someone’s identity.

Alfred C. Kinsey (1894 – 1956) was an American sexologist and professor of entomology and zoology. He devoted a great part of his life to research on the human sexuality that concluded in two landmark publications, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (1948) and Sexual Behavior in the Human Female (1953), collectively known as the Kinsey Reports (Kinsey et al., 1948; Kinsey et al., 1953).

Growing up in a Methodist family, Kinsey suffered from rheumatic fever during his youth. This illness ultimately exempted him from service in World War I. Inspired by his high school teacher, he went to Harvard and received his doctorate in fieldwork entomology in 1917 (Pomeroy, 1982)1. In 1921 he got married to chemistry major and naturalist Clara Bracken McMillen (1898 – 1982) and had four children with her. (Kinsey et al., 2023; Pomeroy, 1982)2.

His professional life initially focused on the study of North American gall wasps and his teaching at the Indiana University. Between 1938 and 1940 an assignment to teach a Marriage Course brought his way further away from the wasps and towards the human sexuality. Inspired by the personal stories of his students, Kinsey applied his zoological fieldwork methods to sexual behavior, using both statistical case histories3 and biological taxonomy to conduct his studies (Pomeroy, 1982).

Together with his associates Wardell B. Pomeroy (1913 – 2001), Clyde E. Martin (1918 – 2014) and later Paul H. Gebhard (1917 – 2015), Kinsey traveled across the U.S., conducting thousands of interviews. This interviewing or “history-taking” was a process of asking an individual approximately 300 questions in “rapid-fire mode” with constant eye-contact, which could take from 90 minutes to 17 hours (Kinsey et al., 2023). His dedication to this work was evident: according to Time magazine, Kinsey worked six days a week and hadn’t taken a vacation in 13 years by 1952 (“Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey,” 1952).

Kinsey was a perfectionistic collector with the goal to collect as many histories as it takes to make his study representative − as is well illustrated in the inscription of the first Kinsey Report (Figure 2; Pomeroy, 1982). Before he could make this goal become reality he died at the age of 62, due to heart problems (Pomeroy, 1982).

The Kinsey Scale

One of the most significant contributions of Kinsey’s research is the development of the Kinsey Scale, first introduced in Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (1948). The 21th chapter of this report considers the “Homosexual Outlet” and reveals that the then prevailing binary labeling of sexuality – dividing individuals into “homosexual” or “heterosexual” − failed to capture the full range and fluidity of sexual experiences. 4

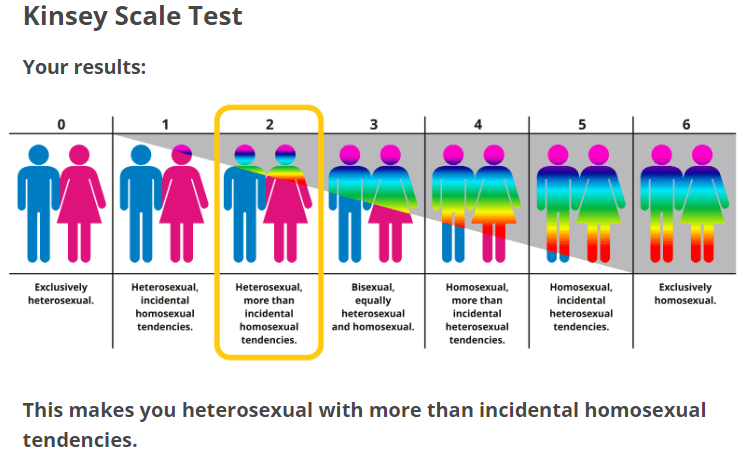

To illustrate the continuum of sexual orientation during a specific period in an individual’s life, Kinsey and his colleagues developed the “heterosexual-homosexual rating scale”, ranging from 0 to 6 (Figure 3)5. Importantly, the position on the scale can change during the lifespan and is determined by the balance of heterosexual and homosexual experiences, not by their frequency.6

Additional to this 0 − 6 scale, Kinsey briefly discusses an “X” category to represent asexuality in his first report. He adds it to statistical charts following the display of the scale, while discussing it later more in-depth in his second report Sexual Behavior in the Human Female. He emphasizes here that all positions on the scale are part of the natural spectrum of human sexuality (Kinsey et al., 1953).

In Kinsey’s studies, participants would not only provide their own assessment of their position on the scale, but their placement was independently rated by two researchers before being mutually agreed upon (Kinsey et al., 1953). This stands in contrast with today´s use of the scale (see “Kinsey Today”).

Over time, the scale has been adapted by various researchers, most notably in the “Klein Sexual Orientation Grid” (Klein et al., 1989), which refined sexual orientation into categories such as attraction, behavior, fantasy, emotional preference, social preference, self-identity, and lifestyle preferences. Other adaptations include the Multidimensional Scale of Sexuality (Berkey et al., 1990) and the Snell Assessment of Sexual Orientation (Snell & Papini, 1989).

Societal Perception on Homosexuality

Before the publication of Kinsey’s report and thereby his scale, people were either labeled “heterosexual” or “homosexual”. Moreover, the public perception of homosexuality was deeply stigmatized. Homosexuality was viewed as rare, therefore abnormal and connected with neuroses and psychoses. Furthermore, homosexuals were considered neither male nor female but persons of mixed sex. Psychiatrists discussed the “homosexual personality”, thus believed that being homosexual correlates with a distinct personality (Bullough, 1998; Downham Moore, 2021; Pomeroy, 1982). Bullough (1998) argues that physicians and psychiatrists of that era were more influenced by societal attitudes and the prevailing cultural zeitgeist than by scientific evidence.

A letter by Kinsey that he send in October 1939 to his fellow scientist and close friend Ralph Voris (1902 – 1940) illustrates the taboo nature of the topic at that time well (Donna J. Drucker, 2010)7. Kinsey privately confided in Voris about sensitive findings that were so controversial at the time that he did not want anyone but his friend seeing them – he wrote about the beginning of taking histories from homosexuals. In this private letter he censored the word homosexual fearing that someone might find it.

That was not without reason. Individuals known to engage in homosexual acts faced severe societal and legal consequences, with consensual same-sex activity still criminalized in the U.S. until 2003 (Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558, 2003)8. Even studying human sexuality was prompt with similar consequences. According to Gagnon (1975) and Kinsey (1948), an academic career could be destroyed by just conducting a study in that field.

However, Kinsey was able to conduct his studies due to several favorable factors that influenced the sociocultural context of his time. He noted in his first report “an abundant and widespread interest in the possibilities of such a study,” which Gagnon (1975) supports, stating that Kinsey’s success was indicative of shifting attitudes in the U.S. toward sexuality research. Since the 1890s, interest in understanding human sexual behavior had been growing.9

Kinsey and his colleagues worked more than a decade on the first Kinsey Report and got relatively little media attention in that time. Gagnon (1975) attributes that to the timing. By the late 1930s, the U.S. was emerging from the Great Depression and preparing for World War II. Public and media focus was on these larger societal issues, and without the rapid dissemination of information that modern mass media provides, Kinsey’s work initially stayed under the radar.

After the Publication

That changed at the 12th of August 1948. The publication of the first Kinsey Report introduced a new way of labeling sexual orientations and marked a turning point in both public discourse and the reception of sex research. While society had become more open to the study of human sexuality compared to a decade earlier, the reactions to the report were still intense. Pomeroy (1982) described it as “the most violent and widespread storms since Darwin,” and Gagnon (1975) viewed its release as a national event, far beyond just a book publication.

Kinsey’s findings, particularly regarding the prevalence of homosexual experiences, directly challenged the psychiatric and societal beliefs of the time. For instance, the report highlighted the gap between legal codes and actual sexual behavior, revealing that many acts considered deviant or illegal were quite common. This started efforts to reform outdated laws that criminalized for example consensual homosexual activity. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, the report’s influence could be seen in movements that embraced slogans like “gay is good” and “out of the closet, into the streets,” as homosexuals began to reject the labels of “sick” or “perverse” (Gagnon, 1975).

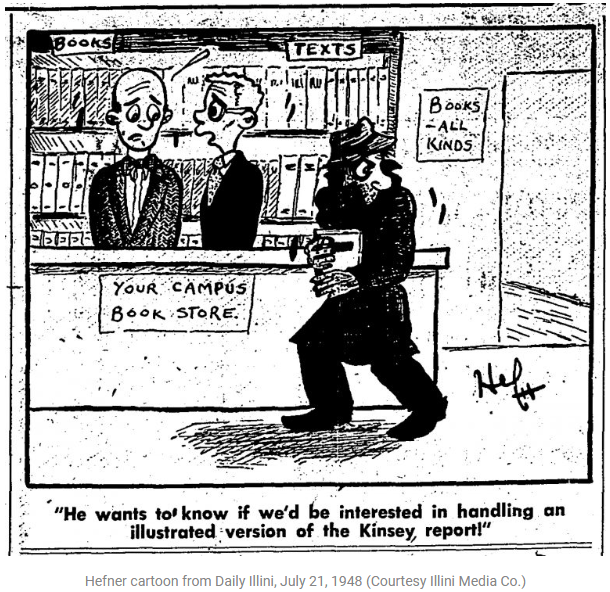

Moreover, the report brought terms like “premarital intercourse” and “orgasm” into mainstream conversation, making discussions about sexual behavior more socially acceptable. Kinsey himself became a household name, with references to his research appearing in media, comedy, and everyday discussions (Figure 5, Gagnon, 1975). His fame was cemented when he appeared on the cover of Time magazine in 1952 (Figure 4, “Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey,” 1952), and phrases like “hotter than the Kinsey report” became a national figure of speech (Gagnon, 1975; Pomeroy, 1982).

However, the report also sparked backlash. In 1953, Protestant groups protested the release of the second Kinsey report (miscellaneous, 1953). By 1954, the American Medical Association accused Kinsey of inciting hysteria, while the U.S. House of Representatives investigated his funding sources (miscellaneous, 1954a). The Philippine Customs Board of Censors even recommended banning the import of the Kinsey Reports (miscellaneous, 1954b).

Despite the controversies, Kinsey’s work shifted the discussion of sex from backroom whispers to mainstream parlors. As Gagnon (1975) put it, “what had been essentially collectively unknown became part of the content of daily life.” The trend continued with factors like the discovery of penicillin, more women entering the workforce, and the rise of the teenage demographic in the mid-1950s, which further strained the old social norms (Hileman, 1953).

Although Kinsey may not have set out to spark a sexual revolution (Kinsey et al., 2023)10, I argue that he paved the way for it by revolutionizing the social point of view on sex and the labeling of sexual orientation.

Kinsey Today

As discussed above, the primary focus of the debate following the publication was the prevalence of homosexuality. The Kinsey Scale itself and its message that the authors see sexuality as fluid did not get as much attention. Pomeroy (1982) concludes in the biography: “Although the scale has not caught on to the degree we thought it would, I think it will become more and more important with time. That was Kinsey’s belief too”.

In many ways, this prediction has proven true. The Kinsey Reports are still recognized as landmark works and have been adapted and discussed by various researchers, remaining a subject of debate even decades after their publication (Shively et al., 1984).

Today, the Kinsey Scale is commonly used in online quizzes and forums, as a way for individuals to discuss and explore their sexual identities by giving them a label (Figure 6). Here individuals often select decimal values rather than whole numbers, illustrating the fluidity of sexual identity that Kinsey intended (Drucker, 2012). Drucker notes that many people appreciate using a depoliticized number on a scale rather than labels like “homosexual,” “bisexual,” or “heterosexual,” which can carry societal or political implications. The scale also provides individuals with a sense of both uniqueness and shared experience, helping them navigate identity formation in a postmodern age.

One challenge with the modern use of the Kinsey Scale is its common application as a self-report measure − something Kinsey did not intend. Kinsey used the scale as a classification tool for researchers, with standardized methodology and independent rating, but today, many studies and online platforms use it in a less structured way. This shift began as early as 1948, when Geoff Gorer labeled it as a self-report tool in The American Scholar (Gorer, 1948). Since then, various studies, such as Kenyon (1968) and those by Rieger et al. (2005), have continued this trend, which can lead to misunderstandings about the scale’s original purpose. Additionally, modern critiques focus on the scale’s failure to account for gender-diverse identities, such as trans and non-binary individuals, highlighting the need for more inclusive frameworks in discussions of sexuality.

While the Kinsey Scale remains influential, the concept of “sexual fluidity” has not yet replaced the dominant view of sexual orientation. In Western culture, the heterosexual-bisexual-homosexual triad continues to shape popular understanding, with Drucker (2012) noting that the Kinsey Scale lacks the visibility and cultural weight to fully reform these categories.

Why labels should not define one´s sexual identity

The practice of labeling sexual orientation has evolved over centuries, with labels and their societal meanings continuously shifting. Originally, the binary system, which stigmatized “homosexuals” and viewed “heterosexuals” as the norm, began to shift in part due to Kinsey’s work. This helped reducing the stigma around homosexuality and turning it into an empowering identity for many. Over the past decades, the label “bisexuality” emerged as an additional category. Although these three labels − heterosexual, homosexual, and bisexual − remain dominant, the concept of sexual fluidity has gained traction. Nonetheless, the persistent need for labeling sexual orientation was evident then and still is in contemporary society.

Kinsey writes in his report that “it seemed desirable to develop some sort of classification which could be based on the relative amounts of hetero and homo experience or response in each history.” Searching for “Kinsey Scale” on Reddit reveals numerous discussions where individuals seek to understand their sexual orientation through this framework11. It seems to be important to not only know to what gender(s) one is attracted but also label that attraction.

But why does it seem desirable to Kinsey and so many others to label their sexual orientation?

To gain understanding on that matter, several perspective need to be considered. on the one hand, labeling influences the individual that labels themselves (personal perspective) and on the other hand the societal view on the labeled individual (societal perspective). Therefore, advantages and disadvantages result from both perspectives.

An individual can gain several benefits from labeling themselves. Having found any favored label like “bisexual” or “On the Kinsey Scale a 3.5”, gives an individual the ability to articulate who they are and thereby find a community of people with similar experiences (Drucker, 2012). British sociologist Mary McIntosh (1968) argued that homosexuals often embrace their label because it gives them a stable identity, allowing them to view their behavior as appropriate for their category, without feeling like they are breaking society’s rules. The label provides them with a sense of legitimacy, which can be crucial in facing societal pressures or discrimination, argues Mary McIntosh.

Furthermore, the label can lead to reduce uncertainty in life. The complex reality of life can thereby be broken down into manageable, understandable categories. This can be beneficial both personally, by aiding self-categorization, and socially, by helping others better categorize the labeled individual.

While personal benefits are evident, societal labeling can lead to stigmatization. According to the labeling theory12, a label can confine or limit individuals, shaping personal and societal perceptions and creating self-fulfilling prophecies. This process, once a label is assigned, can lead to stigma both on personal and societal level (Fein & Nuehring, 1981)13.

At a societal level, labeling someone as “homosexual” can result in them being seen as outside the “norm,” creating a sense of distance between individuals with different labels. Goffmann (1963)14 argued that modern stigmas are driven by societies demand for “normalcy”. This concept of normalcy often leads to labeling and stigmatizing those who deviate from societal norms.

William Dubay (1987) also sees disadvantages of labeling on a personal level: “It solves some problems but creates many more, replacing a closet of secrecy with one of gay identity.” He suggests to reject the homosexual label entirely, choosing not to define themselves as either homosexual or heterosexual, and instead taking responsibility for their own actions without adhering to any label. However, my critique is that completely abandoning labels would diminish or even eliminate the discussed personal benefits of labeling.

Thereby, the challenge is to maintain the personal benefits of labeling while minimizing the personal and societal drawbacks. Kinsey offers a solution to this challenge (Kinsey et al., 1948): “Instead of using these terms [homosexual and heterosexual] as substantives which stand for persons, or even as adjectives to describe persons, they may better be used to describe the nature of the overt sexual relations, or of the stimuli to which an individual erotically responds. “ What resonates with me is that one should not be given a label to define the entirety of their identity but to describe their sexual experiences. I propose aiming to view the labels we assign to our sexual orientation simply as descriptors, rather than allowing them to encompass our entire identity. In the end they are just that – labels that should not be inflated beyond their actual importance.

This approach would, regarding the personal perspective, preserve the advantages of labeling without pressuring individuals to conform entirely to a single aspect of their identity. Of course, the societal perception, which can lead to stigma, can only change if society´s point of view on sexual orientations changes – for example by reducing the demand for “normalcy”.

Conclusion

The Kinsey Scale had a profound influence on societal perceptions of sexuality, particularly at the time of its publication. By challenging the binary view of sexual orientation, Kinsey revealed that human sexuality exists on a continuum, with many individuals falling somewhere between the extremes of heterosexuality and homosexuality. This reshaped societal understanding, reducing the stigma around homosexuality by showing that it was more common than previously believed. The publication of his reports in the 1940s and 1950s sparked widespread debate, marking a turning point in how society approached conversations about sexuality.

In the decades following the reports, the influence of the Kinsey Scale persisted, contributing to the gradual de-stigmatization of homosexual and bisexual identities. Although resistance to these ideas remained, Kinsey’s work paved the way for more open discussions about sexual fluidity and identity, influencing both academic research and public discourse. Today, the Kinsey Scale continues to be referenced, especially in online communities, as a tool for understanding the diversity of sexual experiences.

However, the topic of labeling remains central to the discussion. While labels provide clarity and a sense of identity, they also risk limiting individuals by confining them to categories. Kinsey himself proposed using labels not as definitions of a person’s entire identity, but as descriptors of their experiences. This approach would allow for the benefits of labeling − such as self-understanding and community − while minimizing the drawbacks of rigid categorization.

I believe, as societal norms evolve, reducing the pressure to conform to narrow definitions of sexuality can lead to a more inclusive understanding of sexual identity.

References

Berkey, B. R., Perelman-Hall, T., & Kurdek, L. A. (1990). The Multidimensional Scale of Sexuality. Journal of Homosexuality, 19(4), 67–88. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v19n04_05

Bullough, V. L. (1998). Alfred Kinsey and the Kinsey report: Historical overview and lasting contributions. Journal of Sex Research, 35(2), 127–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499809551925

Donna J. Drucker. (2010). “Building for a life-time of research”: Letters of Alfred Kinsey and Ralph Voris. Indiana Magazine of History, 106(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.5378/indimagahist.106.1.0071

Downham Moore, A. M. (2021). The Historicity of Sexuality: Knowledge of the Past in the Emergence of Modern Sexual Science. Modern Intellectual History, 18(2), 403–426. https://doi.org/10.1017/S147924431900026X

Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey. (1952, December 15). Time Magazine. https://time.com/archive/6885203/personality-dec-15-1952/

Drucker, D. J. (2012). Marking Sexuality from 0–6: The Kinsey Scale in Online Culture. Sexuality & Culture, 16(3), 241–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-011-9122-1

Dubay, W. H. (1987). Gay Identity: The Self Under Ban.

Fein, S. B., & Nuehring, E. M. (1981). Intrapsychic Effects of Stigma: A Process of Breakdown and Reconstruction of Social Reality. Journal of Homosexuality, 7(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v07n01_02

Gagnon, J. H. (1975). Sex research and social change. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 4(2), 111–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01541078

Goffmann, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity.

Gorer, G. (1948). Justification By Numbers: A Commentary on the Kinsey Report. The American Scholar, 17, 280–286.

Kenyon, G. S. (1968). Six Scales for Assessing Attitude toward Physical Activity. Research Quarterly. American Association for Health, Physical Education and Recreation, 39(3), 566–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/10671188.1968.10616581

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual behavior in the human male (Eighth Printing). Indiana University Press.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (with Allen, J. A.). (2023). Sexual behavior in the human male (Anniversary edition). Indiana University Press.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., Martin, C. E., & Gebhard, P. H. (Eds.). (1953). Sexual behavior in the human female. Indiana University Press.

Klein, F., Sepekoff, B., & Wolf, T. J. (1989). Klein Sexual Orientation Grid [Dataset]. https://doi.org/10.1037/t39167-000

Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/539/558/

McIntosh, M. (1968). The Homosexual Role. Social Problems, 16(2), 182–192. https://doi.org/10.2307/800003

miscellaneous. (1953, September 7). Protesten tegen nieuw Kinsey-rapport. De Tijd: godsdienstig-staatkundig dagblad, Pagine 5. Delpher.

miscellaneous. (1954a, January 7). Kinsey wordt verhoord. Algemeen Handelsblad. Delpher. https://www.delpher.nl/nl/kranten/view?query=Alfred+Kinsey&coll=ddd&page=3&identifier=KBNRC01:000040248:mpeg21:a0065&resultsidentifier=KBNRC01:000040248:mpeg21:a0065&rowid=1

miscellaneous. (1954b, March 6). Dr. Kinsey´s rapport “ontuchtig” verklaard. Java-bode: nieuws, handels- en advertentiebald voor Nederland. Delpher. https://www.delpher.nl/nl/kranten/view?query=Alfred+Kinsey&coll=ddd&page=2&identifier=ddd:010861767:mpeg21:a0016&resultsidentifier=ddd:010861767:mpeg21:a0016&rowid=5

Pomeroy, W. (1982). Dr. Kinsey and the Institute for Sex Research. Yale University Press.

Pomeroy, W. B. (1982). Dr. Kinsey and the Institute for Sex Research. Harper & Row.

Rieger, G., Chivers, M. L., & Bailey, J. M. (2005). Sexual Arousal Patterns of Bisexual Men. Psychological Science, 16(8), 579–584. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01578.x

Shively, M. G., Jones, C., & De Cecco, J. P. (1984). Research on Sexual Orientation: Definitions and Methods. Journal of Homosexuality, 9(2–3), 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v09n02_08Snell, W. E., & Papini, D. R. (1989). The sexuality scale: An instrument to measure sexual‐esteem, sexual‐depression, and sexual‐preoccupation. Journal of Sex Research, 26(2), 256–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224498909551510

Footnotes

- Wardell B. Pomeroy (1913 – 2001), the second author of the Kinsey Report, worked closely with Kinsey for over a decade. In writing Kinsey’s biography, Pomeroy had access to extensive resources, including the archives of the Kinsey Institute, which contained for example 45,000 letters, as well as his own personal memories of their collaboration. His perspective and access to primary sources make him a valuable and reliable secondary source. ↩︎

- In the 2023 Anniversary Edition of the first Kinsey Report Historian Judith A. Allen (1955 – 2024) writes the introduction. There she gives some personal information about Kinsey and his time. She worked more than three decades at the Kinsey Institute and the Indiana University as a Senior Research Fellow, Historian and Professor. Her perspective and access to primary sources make her a valuable and reliable secondary source. ↩︎

- In the context of Kinsey’s research, ‘histories’ referred to detailed personal interviews in which participants were asked about their sexual experiences and behaviors. The term ‘histories’ reflects the method’s emphasis on gathering full accounts of each participant’s sexual life over time, allowing for a deeper understanding of human sexuality. ↩︎

- Kinsey emphasizes in the 21th Chapter of the first Kinsey Report: “Males do not represent two discrete populations, heterosexual or homosexual. The world is not to be divided into sheep and goats. Not all things are black nor all things white. […] Only the human mind invents categories and tries to force facts into separated pigeon-holes. The living world is a continuum in each and every one of its aspects. The sooner we learn this concerning human sexual behavior the sooner we shall reach a sound understanding of the realities of sex.” ↩︎

- A rating of 0 represents individuals whose sexual and emotional experiences are exclusively with the opposite sex, while a rating of 6 indicates exclusive same-sex experiences. ↩︎

- For example, two individuals with differing amounts of sexual encounters—one with equal experiences of both types and another with double—could still be positioned at the same point on the scale. ↩︎

- Donna J. Drucker is a historian, whose expertise lies in 20th-century U.S. and Europe. She wrote a book on Kinsey and various papers. She reproduced the letters between Voris and Kinsey with permission from the Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender,

and Reproduction, Inc. ↩︎ - Kinsey himself highlighted this in his report, stating: “The high school boy [who engaged in homosexual acts] is likely to be expelled from school and if in a small town, he is almost certain to be driven from the community.” ↩︎

- Which lead to the creation of the Committee for Research in Problems of Sex (CRPS) in 1921, specifically aimed at conducting general studies on sexual behavior in America (Bullough, 1998). ↩︎

- Kinsey is often said to be the “father of the sexual revolution” ↩︎

- For example, one user questions, “I got a 2 on the Kinsey Scale; does that mean I can classify myself as bisexual?” (@Yppah118), while another reflects, “Where are you on the Kinsey scale? Last year I would’ve said 3.5, but now I feel like 5.4” (@Foremun2). ↩︎

- Labeling theory developed among sociologists in the 1960s, largely influenced by Howard Saul Becker’s book Outsiders. This book was pivotal in popularizing the theory, which examines how societal labels, such as “deviant,” shape individuals’ self-identity and behaviors. ↩︎

- Sara Fein and Elaine M. Nuehring (1981) state that once someone is labeled as gay, that label becomes their “master status,” meaning it dominates how others view them and how they see themselves. This can limit the person’s ability to define their own identity and prioritize different aspects of their personality. For example, newly out individuals might struggle because their past and present actions are now interpreted through the lens of their sexual orientation, leading to a loss of control over how they are judged by others. ↩︎

- Erving Goffman, a highly influential sociologist, made significant contributions to labeling theory. ↩︎